The voyage of the sardines in oil – or Waiting for Pierrot

Philippe CausseWhen we were contacted at the beginning of August by a television editor who wanted to shoot a report on the subject of vintage sardines and needed our help for this, I had no idea that just under 2 months later I would only be wearing rubber slippers on my feet and a lime green surgical cap on my I would decapitate and gut a sardine with my own head and shortly thereafter bravely venture into 2 meter high waves on a small nutshell to go sardine fishing in the dark of night ... But life has many a nice surprise in store for you. Let's start at the beginning:

With our help, Daniel Mohr's team (Kabel 1 - "Abenteuer Leben" editors) was able to make an appointment at the Conserverie Gonidec in Concarneau. From there we get the fantastic sardines and vintage sardines "Les Mouettes d'Arvor". The company was founded in 1959 by Jacques Gonidec, I. The so-called vintage sardines have been produced here since 1996 under the brand name "Les Mouettes d'Arvor", a defunct local football club to which Jacques Gonidec II belonged. It is now used by Jacques Gonidec, III. guided. We already knew him and his wife Valérie from a trade fair, but had not yet made it to Concarneau to visit them at their place of work. That's why I selflessly offered Daniel my services as a mediator and translator, and that's how I was allowed to accompany the team.

Two days before departure, they paid us a visit to the store to film the first scenes. Some of our Berlin customers may still remember the LED lamps, the unfamiliar equipment, the many cables and the strange men in the store...

And then it started: I met the "guys" (Daniel Mohr, editor / Matthias Barth, camera / Roland Röhrig, sound) in Paris at the airport. From there we continued our journey to Brest, and the next morning by rental car to Concarneau. It was my first visit to Brittany and I was accordingly excited.

In Concarneau we visited Jacques Gonidec in his Conserverie and were personally led through the sacred halls by the host, so that we were able to get a first impression.

But it didn't really start until the next morning. The trip to the lake with a sardine cutter that might have been planned for the first evening had to be postponed because of the bad weather – a storm with violent gusts, waves up to 3 meters high and rain.

And so the next morning we were relatively rested and on the mat at 8 a.m. sharp, ready to throw on our outfit appropriate for the occasion and to accompany the production process of the vintage sardine from start to finish.

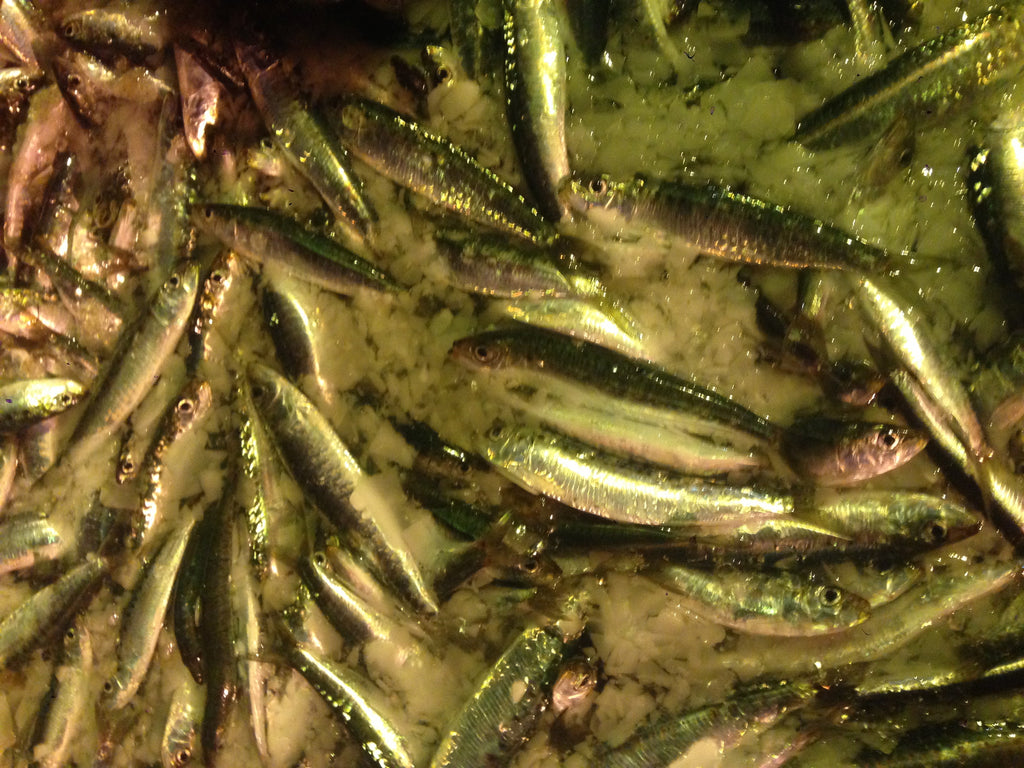

It starts with the delivery of the sardines caught the night before in front of Concarneau or one of the other nearby towns (Lorient, Brest, Quiberon).

In the Conserverie they are first washed and then taken to the so-called "Dirty Room". There the workers remove the heads and intestines of the fish by hand and with a sharp knife. The handles are practiced and everything happens so quickly that you hardly notice what is really happening. I was allowed to try it once and had to realize that it wasn't that easy. It is important to cut through the central bone, so to speak, in the neck with a quick and precise cut and then, without stopping, to pull the intestines out of the stomach with a determined pull. It is fundamentally important not to cut up the intestines and, above all, to really remove everything, because the intestines are not easy for the human organism to digest. With cheaper products, machines do this job, and they often fail to be as thorough, careful, and gentle as the skilled workers. This explains, among other things, why hand-processed sardines taste so much better. My first two attempts fail miserably and elicit Monsieur Gonidec to comment that I should treat the sardine with more respect. He shows me how carefully I have to touch the fish and, above all, where: the thumb must be placed just below the gills, the remaining fingers should only gently enclose the sardine. It actually gets better that way and the third sardine I cleaned makes it into the line of those who move on to the next step.

Next, the sardines are washed again in salt water or soaked for about 3 minutes. They are then dried in a special drying facility at 57°C. These two steps, which are part of the preparation "à l'Ancienne", form a thin crust of salt around the sardine, which becomes crispy when it is fried in sunflower oil at 100°C. But it is much more important that this crispy skin keeps the sardines from drying out, because there is a thin layer of fat under the skin, which – if it stays there – ensures that the sardines are nice and juicy and therefore aromatic. This is also a step that fewer and fewer conservatories are still taking. This saves them production costs, but their products lose significantly in terms of quality and taste.

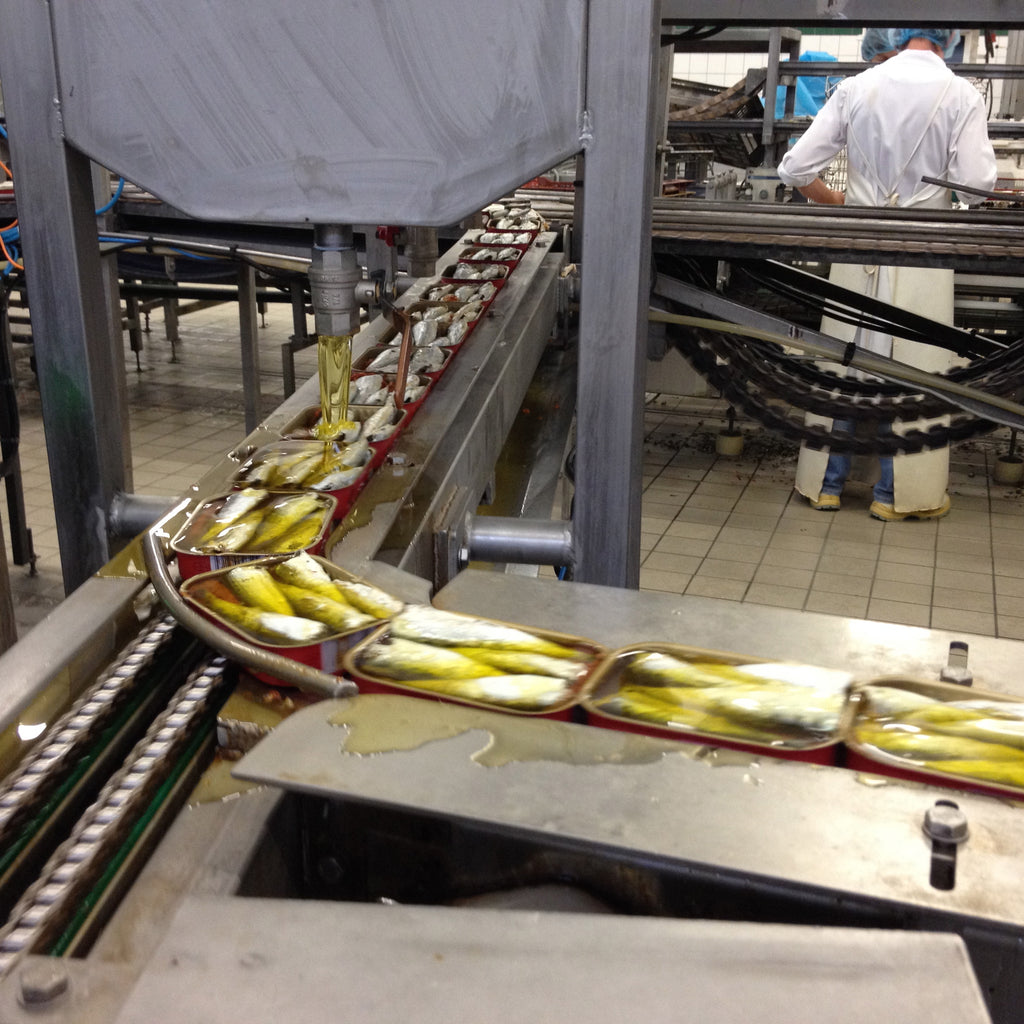

After the sardines are fried, they are hung for at least 2 hours so that the sunflower oil and the good olive oil don't mix with each other later.

After the lunch break, work continues in the next, much cooler production room next door. When we return from our lunch break with Monsieur and Madame Gonidec (in "La Coquille", a very pretty and busy restaurant on the port of Concarneau, where the Gonidecs are greeted with kisses), the hard-working women are already back on the treadmill.

A special edition is being produced today: the vintage sardines from the special collection series "Brest 2016". A really nice tin, which we will certainly order when the time comes.

Now the sardines are trimmed again, this time with scissors, again by hand. A bit of the tail and the head end still have to come off. On the one hand, so that the sardines fit perfectly in the can, on the other hand, to get a really clean and flawless product. The cans are then filled with the finest cold-pressed olive oil before they are fitted with lids and then sterilized in a special facility for one hour and 40 minutes at 120°C.

We soak up all the information with inquisitiveness and curiosity, interview the workers, take photos and marvel at the sophistication of the systems and the dexterity of the ladies on the assembly line. Many of them have been working in the factory for 18 or 20 years, starting under Monsieur Gonidec's father. It's really hard for me to imagine, because it quickly becomes clear that this is a tough job...

Unfortunately, throughout the day there was also the anxious suspicion that this time it would not work again to accompany a sardine cutter on its nightly catch, because the weather had actually gotten worse and again no captain wanted to take us with them. In retrospect, I have to admit that I'm quite happy about that, now that I know how much a ship rocks even when the sea is less rough...

So we slowly had to get used to the idea that we would probably not be able to experience this stage of the journey of the vintage sardine live and went to bed a bit dejected.

However, the storm abated overnight and so, just as we were on our way to the airport, we received a call from Monsieur Gonidec: he had found a captain who would go out in the evening and would also be willing to take us on board take. We allowed ourselves a brief pause to celebrate, then the sound man hit the brakes and turned around. Daniel quickly made a couple of calls to extend our trip by a day at short notice and finally we reprogrammed our lisping sat nav to Lorient. Because there we would meet Pierrot le Pluhart in the evening, the captain of the sardine cutter "L'Étoile Polaire" - the polar star.

When the time finally came, I could hardly believe it. After two days of waiting with an uncertain outcome, I was standing at the harbor in my fishing outfit, equipped with dry bread and travel chewing gum, when Pierrot and his boys arrived.

Pierrot is 61 years old and has been at sea since 1968. Actually, he's been retired for 5 years, but he just can't stay on land. He's now committed to retiring within the next year, but after getting to know him a bit, I'm not entirely sure if he'll actually make that plan a reality. When I asked what his wife said about him going out every night, he simply said, "She knows I love it, so she doesn't mind."

Pierrot's crew of eight is remarkably young, all of them in their early to mid-twenties and highly motivated. He got his boys together about 3 years ago and is very happy with them. He has known some of them since they were little boys, because their fathers were also fishermen and sometimes went to sea with Pierrot. The crew works perfectly together. When things get serious, every move is spot on and communication works even with just a few words.

The mood on the small cutter is good right from the start and we feel very welcome. Everyone willingly provides information and explains in detail how everything works. And so we leave the bay – after we've quickly refueled and loaded ice cream – with the sky still blue and some sunshine. The sea seems calm and I still can't imagine it getting wilder later. But as soon as we leave the bay, Pierrot warns that it will rock now. And he's right: as soon as we go out onto the open sea, the waves roll in and pile up to around 1.70 m. The little nutshell takes every wave, crashing into its valleys and riding up its slopes. The boat not only rocks top to bottom but also left to right and I'm glad all the fish tanks are well moored. Pierrot is drinking tea in his captain's chair in the pulpit and there is nothing to be seen of the crew: they have retreated to the cabins in the hold of the ship, in which none of us four newcomers would probably endure even a second. We stare at the horizon and try very hard to keep our composure. If these comparatively small waves have such an effect, I'm really glad that we didn't insist on a trip on one of the previous days. And I'm thankful for my rubber boots!

After about an hour and a half - the sun has almost completely disappeared - Pierrot discovers a large spot on his sonar at the presumed point he had been heading for for the past few days. He suspects it could be a school of sardines. One of the ship's boys is just explaining to me the principle of "pêche à la bolinche" (the traditional Breton way of fishing with a special net), and the keyword "boué!" (buoy) echoes through the night. From there everything happens very quickly and before we know it, the first silver sardines are already wriggling in the net.

With just one catch "we" catch 5 or 6 tons of sardines of a respectable size that evening Nobody knows exactly afterwards ... About 600 kilos of them are sold to local fish sellers that night for 2 - 3 € per kilo. The rest goes to wholesalers and conservatories early in the morning for €0.75. Jacques Gonidec will buy half of "our" catch and use it to make his vintage sardines.

Digression: La pêche à la bolinche

This type of fishing is a Breton tradition that allows gentle fishing with almost no bycatch and does not destroy the seabed. The net is constructed like a large, wide band, with floats attached to one side and heavy iron rings on the other, through which the net sinks up to 40 meters deep. Ropes are also attached to these rings at both ends, with which the net is closed at the bottom. One end of the net is fixed to the boat and a buoy is attached to the other end. This is thrown into the water when a school of sardines appears on the sonar. The boat then moves in a fast circle so that the net slides into the water and tightens around the catch. Now the full net can be pulled up until the fishermen, using a small crane and a small net that works on the same principle, can fish the fish out of the net as if with a scoop and transfer them to ice water tanks on board.

The network in numbers:

- Dimensions: 330x83m

- Reachable depth: 40m

- Costs: around €30,000

- Weight: 1.5t

Exhausted, happy, hungry and a little unsteady on our feet, we arrive back at the port around midnight. Now it's time to say goodbye to Pierrot and his boys. But maybe the farewell won't last too long, because together with my father and my sister we are planning a joint trip through the Conserverien in June - from Concarneau (Gonidec, Les Mouettes d'Arvor) via Quiberon (La Quiberonnaise and La Belle-Iloise) to Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie (La Perle des Dieux). Of course we will also make a detour to the port of Lorient to see if Pierrot is still at the helm and takes us three landlubbers back on board ...

- - -

A few more impressions:

For those who prefer to watch than read, here is a short film about the trip: